‘In the field of architecture and urban design, I take postmodernism broadly to signify a break with the modernist idea that planning and development should focus on large-scale, metropolitan-wide, technologically rational and efficient urban plans, backed by absolutely no frills architecture.’ (David Harvey, 1990)

Harvey focuses on both modern and post-modern architectural buildings in New York and how they contrast.

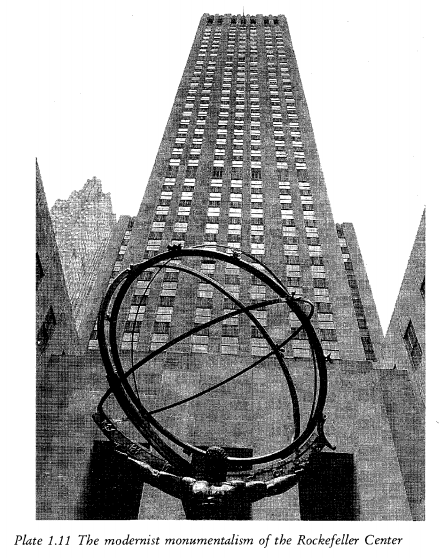

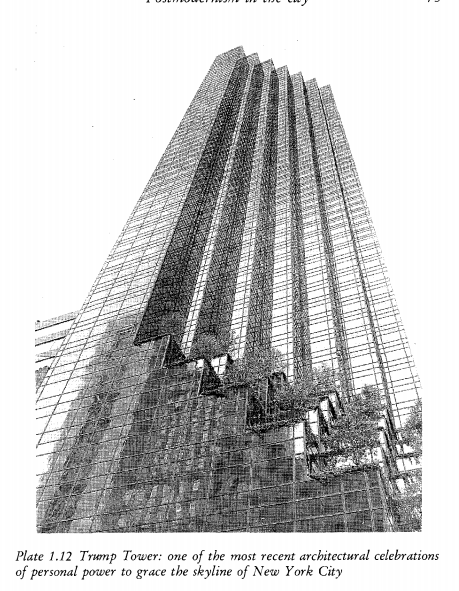

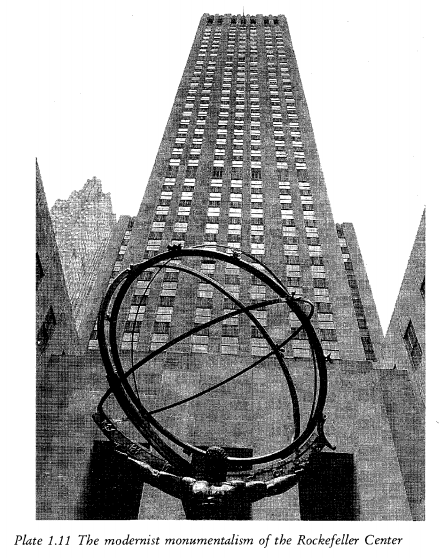

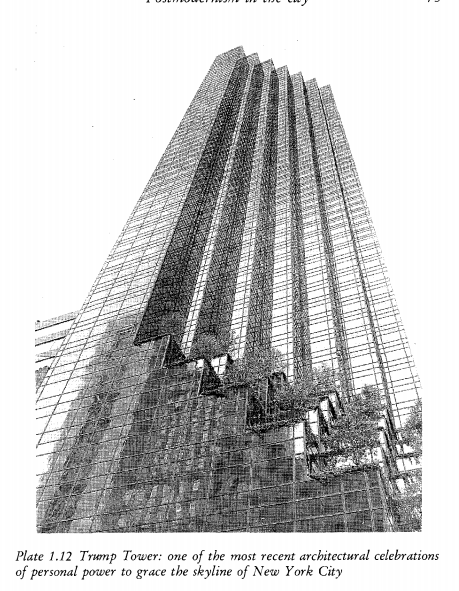

Harvey looked at the contrast in the Rockefeller building and Trump Tower and how post-modern buildings have drastically changed the appearance of many buildings in the city. The Rockefeller presents a dull, concrete building with no fascinating features unlike the Trump Tower that has many dimensions made from glass and tree’s placed on the building.

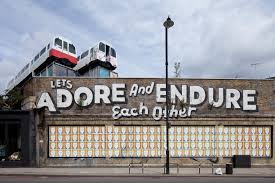

East London similarly has both modern and post-modern buildings that majorly contrast. All the postmodern buildings are seen as fascinating and interesting architectural buildings because of the material and design that has been used such as the Gherkin and the Lloyds Tower.

This image shows the clear contrast between modern and postmodern housing in East London. (Stratford)

Harvey’s views on the concepts of space and urban planning:Postmodern urban planning attitudes differ to modernist attitudes with regards to the use of space. Harvey explains the differing concepts by outlining architect Leon Krier’s criticisms of modernist urban planning as being overly focused on the circulation of people to ‘mono-functionally zoned’ areas that may include, for example a skyscraper or a central business district.

Krier finds modernist urban planning to be wasteful of land and energy and on the whole, anti-ecological and his vision of a ‘good city’ is one that is considerate of the environment and the community. Krier’s approach to urban design calls for all urban functions to be within comfortable walking distance and like many postmodernists, Krier seeks a return to traditional urban values by creating ‘cities within cities’.

Because of modernist ideals of monofunctional zoning and “rational planning” of space “circulation systems” were created to generate systems of productivity and growth but these “artificial arteries” generalise individuals and group them as the same.

Harvey moves on to describe the Western industrialised world’s post World War II reluctance to return to the enormous economic problems that were experienced during the 1920s and 1930s.

While post-World War II Britain employed modernist systems of constructions, urban planning was subject to strict country planning policies that restricted suburbanisation and forced people in to the city. Although these urban planning policies led to the removal of slums to make way for factories, hospitals, schools and prefabricated home, there was growing concern for spatial patterns and the impact of modernist urban planning on the promotion of equality.

In post World War II Europe, many cities required rebuilding after the destruction caused by the war. In the United States however, construction was driven not by damage to metropolitan areas but by a bolstered economy. The United States utilised modernist mass production techniques and experienced fast, loosely controlled suburbanisation which was largely assisted by the development of highways and other infrastructure. The US still relied upon mass production and backing from the Government but mainly focused on private development. As people and employment began to spread outward however, inner cities began to suffer from deterioration which resulted in government subsidised initiatives that aimed to renew metropolitan areas. Due to the reluctancy of returning to enormous economic problems after World War II and the need for reconstruction of social spaces, mass production and planning was adopted.

Harvey highlights the fact that modernism and fordism go hand in hand with capitalism with the need for rapid reconstruction and corporate capital still had a great deal of power in property development to build profitably, quickly and cheaply. This was a major branch of capital accumulation.

Harvey is criticises postmodern urban spatial planning because he claims that it fails to convey authentic urban identity. Harvey further states that postmodern urban planning is all too often gentrified, monotonous and significantly influenced by a desire to attract consumers. (Harvey, 1990)

Post by: Abi Groves, Georgina Miles, Marta Santillana, Sheldon Richardson, Dianne Bonney

References:

Harvey, D. (1990). The condition of postmodernity. Oxford [England]: Blackwell.